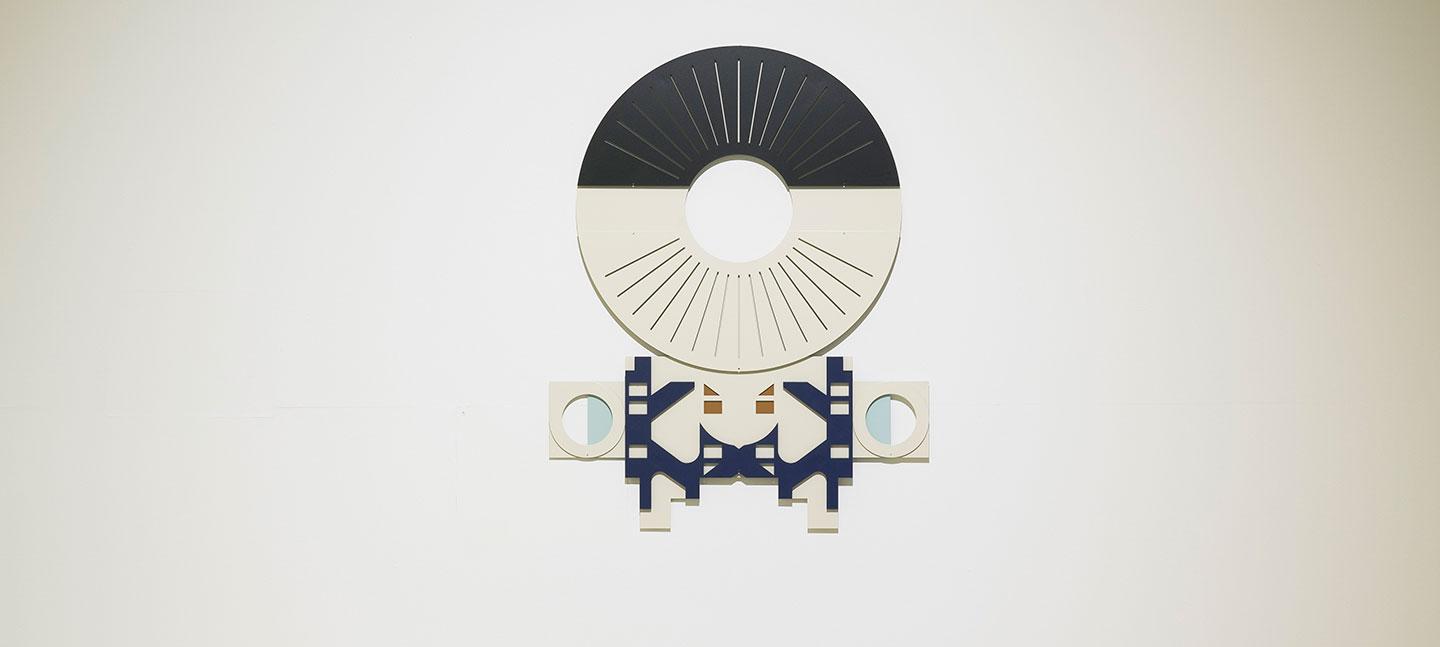

Drawing inspiration from architect Sir William Chambers’ 18th-century drawings for Somerset House, Sayal-Bennett has created a new series of sculptures installed in multiple locations around the site. She is interested in how the British colonial imagination and imperialist attitudes of the time were encoded in the designs of his buildings. Chambers drew upon the classical architecture of the Greek and Roman traditions as well as architecture from East Asia. Similarly, to make her artworks, Sayal-Bennett quotes fragments of his original drawings and remixes them into new geometric abstractions. Her pattern-rich designs are rendered in powdercoated laser-cut steel, resulting in sculptural reliefs that reflect on the past as well as look to the future.

Amba-Sayal-Bennett,-Studio-Portrait,-BSR,-photo-by-Luana-Rigolli.jpg

Q&A with Amba Sayal-Bennett

How did you begin your research for this commission?

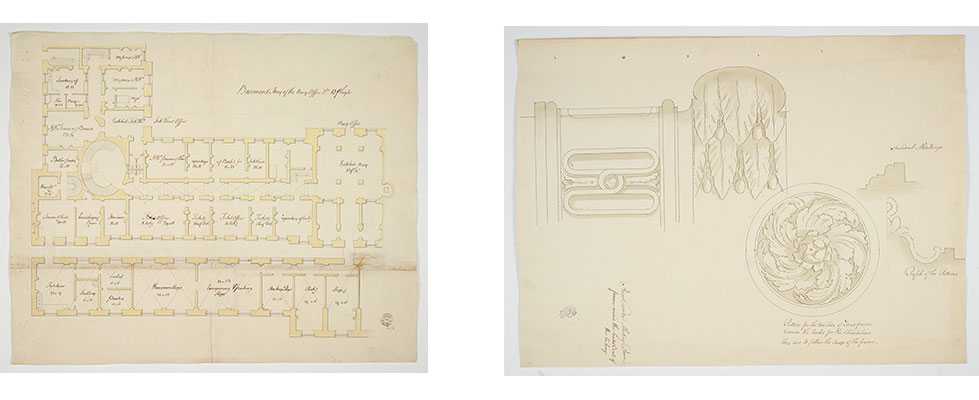

I began to form my research through site visits, reading about Somerset House’s history, and visiting the Sir John Soane’s Museum to see original architectural drawings by Sir William Chambers. There are approximately seven hundred drawings of Chambers' design for Somerset House within their collection. It felt quite surreal to physically handle material from the eighteenth century and to see the drawings up close, complete with broken wax seals and Chambers’ own handwriting.

From that research, what was your starting point for the project?

I started by tracing moments within the history and architecture of the site where processes of abstraction had been informed by the colonial imagination. During the eightieth century, the site was home to the Royal Navy and the Royal Society, a time when the quest for scientific knowledge began to align with British aspirations for Empire. By mapping the Pacific, laying claim to ‘virgin lands’ and experimenting with naval technology, the researchers of the Royal Society extended the boundaries of the British imperial vista, and provided practical help in gaining control over it. Abstraction, here in the form of mapping, was therefore used as a method of division, carving up space to consolidate power.

William-Chambers-Somerset-House-Plans-7.jpg

How do you see those aspirations for Empire as being encoded in the architecture?

Chambers designed the first mosque in Britain which appeared as a folly in Kew Gardens in 1763, alongside the Chinese Pagoda that remains there today. These served as representations of non-European cultures to a Western audience, symbols of distant Others. This orientalist practice of representing cultures encountered through the colonial enterprise, as exotic, idealized, picturesque and sometimes fantastical, was a familiar trope in Europe through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Within Chamber’s history of design, abstraction served to de-contextualise and appropriate architectural forms in the representation of non-western cultures. In his designs for Somerset House, Chambers drew on the principles of classical architecture from the Ancient Greek and Roman traditions, further embedding legacies of Empire into the fabric and history of the site.

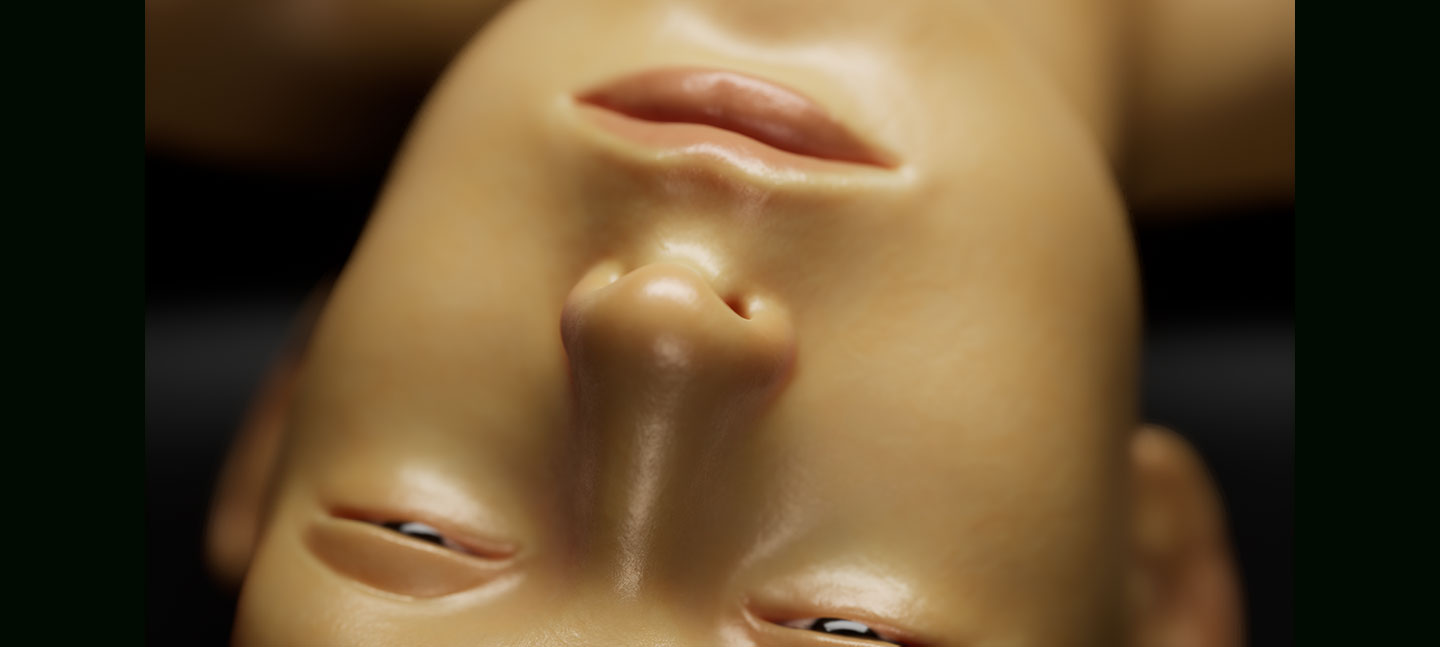

Geometries-of-Difference-Portrait-1.jpg

How have you responded to the history and architecture of the site?

When I started thinking about how to respond to this context, there seemed to be a question around inheritance. How can we develop ways to critically engage with this architecture and its legacies? In the designs for this work, which draw directly from Chamber’s plans for Somerset House, I have used translation as a strategy of misuse. I was thinking about misuse as a form of ‘disobedience’. By not respecting the designs which are part of a colonial legacy, and not using them for their intended purpose, I was interested in exploring misuse as a form of refusal.

What was the process of incorporating Chambers’ drawings into your designs?

I incorporated architectural drawings by Chambers into my designs because they are abstractions of the site itself. Within the works, shapes and forms are isolated from the original drawings by Chambers. These are redrawn digitally and reimagined through a process of speculative translation. Rather than using the drawings according to their original intention, the diagrams function as a set of organising principles within which improvisation can play. Digital re-drawing becomes an act of reinvention on a new site. There are some interesting moments in Chambers’ drawings where the ink bleeds, or where the forms are roughly sketched, freeing them up from being purely instructive and giving them a sense of their own agency. I found that at a material level there is a resistant logic present in the drawings, something that goes against rigid functionality, and gestures which remain in excess of the designs.

William-Chambers-Somerset-House-Plans-8.jpg

The ten works that make up the installation are multi-layered reliefs made of metal – could you say more about your choice of materials?

Within Chambers’ diagrams there is a collapsing of space, whilst aerial views and cut-throughs present impossible perspectives, exposing the materials and layers within the building’s construction. The flatness of the work draws on the language of prototyping as well as architectural drawing and modelling, things that exist in both two and three dimensions. The sculptures are made from powder-coated mild steel as metal has a strong relationship to paper. As a sheet material it bends and folds, and through welding or slotting it moves between two and three dimensions almost instantaneously.

Geometries-of-Difference-Portrait-2.jpg

Could you explain your distinctive style, which combines different methods, from drawing to laser-cutting.

Whether I am using a drawing stencil in my works on paper or a computer modelling program, I am interested in how, rather than being passive tools, these processes have an active role in the development of the work. Through experimenting with different methods, new tools can disrupt previous ways of working. For example, my sculptures have changed through my familiarisation with computer-aided design and the program’s ability to articulate certain forms. The tools and technology that I use are encoded in the work through the traces that they leave behind, creating an evolving and hybridized aesthetic.