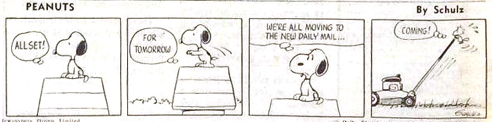

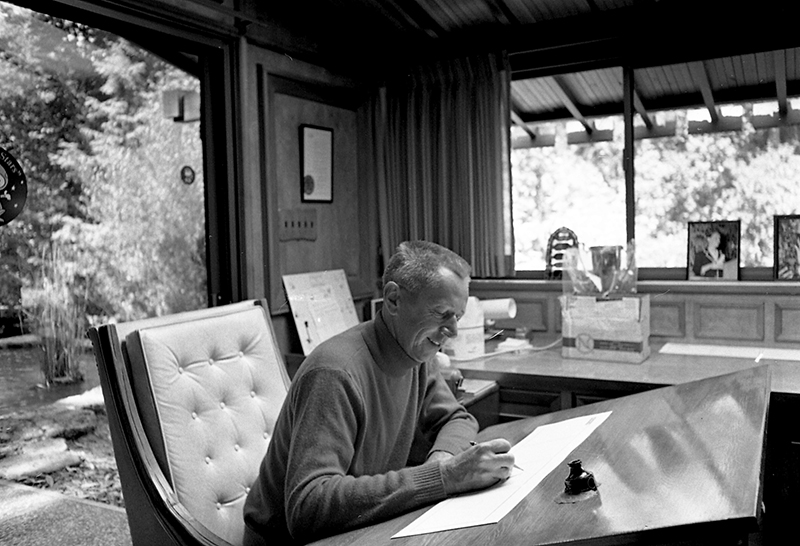

Whilst researching her new artwork for our exhibition Good Grief, Charlie Brown!, Somerset House Studios resident Eloise Hawser uncovered a hidden history of Peanuts in the British press.

When I was asked to be in the Good Grief, Charlie Brown! show, I thought back to my first encounter with Peanuts: a meandering animated love story called Snoopy Come Home, which I had watched over and over as a child. I remembered how the characters navigate the adult world of hospitals, libraries and bookshops; a world haunted by the refrain, “No Dogs Allowed”. Like the show’s curator Claire Catterall, I was curious to understand the impact of Peanuts on this very ‘adult’ world, through its often profound themes, as well as its long-standing appeal for UK audiences.

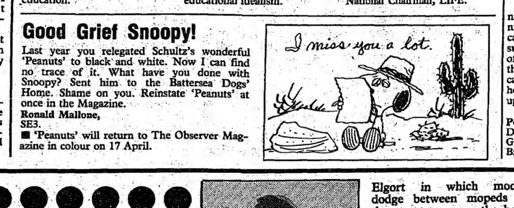

At the beginning of my research for the exhibition, I came across a letter that suggested the loyal affection that Schulz inspired in British readers. A letter to the Guardian from 1988 wanted to know why the strip had not appeared as usual, asking for it to be “reinstated at once”. It even asked the editors whether Snoopy had been sent to Battersea Dogs Home.

Good Grief Snoopy!.jpg