Hyphen-Labs (whose Gospel According to Yawn features in the Sleep Mode broadcast on Friday night) wrote:

"The work never stops, we inject sleep and play into our lives whenever we can. Our average arrangement is work 11 hours; sleep 7 hours; play 4 hours. The hours are flexible and change depending on the project, but art, and thus, our work, is intertwined between our waking and dreaming minds."

The different members of Hyphen-Labs all had different equations for their division of time (work 3 hours; sleep 4 hours; play 17 hours), not all of which added up to a normal 24-hour day.

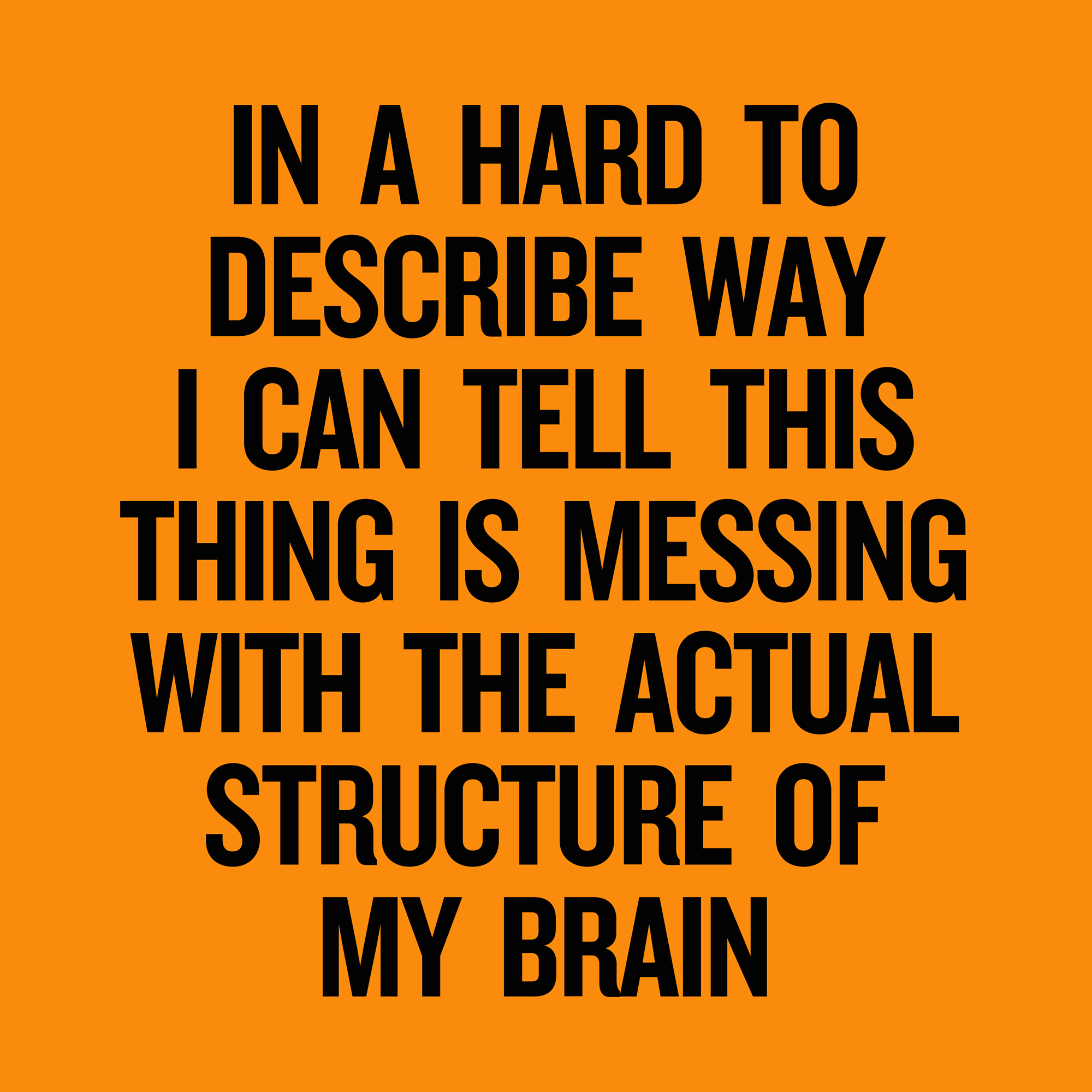

Douglas Coupland (whose Slogans for the 21st Century were the mantra of 24/7 and are the new mantra for life in lockdown) wrote:

"I’m a sleep freak. I get nine and a half hours every day of my life, and it’s why I’ve been self-employed since 1988 – I’ve based my entire life on getting those nine and a half hours, and it’s why I never do a morning radio or TV work or take early flights. Sleep always comes first."

It struck me that when asked about their sleep, most artists instead talked about their work. As a curator it is essential I ask artists about their work, but I’ve learned that I should ask all artists about their sleep, in part because of the way they often juggle the practice of making art with other forms of labour, whether self-employment or freelance contract work. Lockdown has exposed the fragility of those routines in professional and personal lives.

A favourite book of mine, Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Artists Work, details the eccentric working (and sleeping) routines of great creative people and is the ideal counterpoint to the 'highly effective habits of successful people' - genre of motivational or self-help guidebook which usually crowd out the novels on the shelves of an airport bookstore (buying a book before boarding a plane - remember that?). Georgia O’Keefe would take her half-hour walk before breakfast at 7 a.m. (hot chili with garlic oil, eggs, bread, jam, fruit, coffee) and then paint all day, with a lunch at noon and light supper at 4.30 p.m. so that her evenings were free for a long drive in desert. Proust didn’t leave his bed, and wrote, ate, and drank there; Mozart was up and had his hair done by 6 a.m. before a day of composing, teaching and attending concerts. Curators too have particular work/sleep routines: Hans Ulrich Obrist famously commented that he used to sleep 15 minutes every three hours. Me? I sleep a solid 7 hours but wake most nights at about 4.33 a.m. and listen to the silence - or the dawn chorus - before falling back into dreamland.

I, like others, find that the pressures of work shape the times of the day I can switch off. This is more evident during lockdown when the other thing that used to shape my work time - travel - is not possible anymore. Working on 24/7, the meetings to develop the exhibition were measured in increments of time, which started out stretched and unstructured, and then became fixed the closer we got to deadlines. The six hours on the train from home in Scotland to work in London served as time for me to read and write so that the eight hour day could be scheduled with meetings. My own recognition of the distinction between my working time and my leisure time was often determined by external factors and technology: laptop battery power left; wifi speeds; my phone telling me whether the article is a long read or a two minute read; the failure of the power coupler on the train’s engine resulting in a delay. As cultural theorist Sarah Sharma points out in her essay Speed Traps and the Temporal, discussions of time spent tend to be about pace (how efficient or fast are you?) rather than about how time constraints shape us as citizens in a shared society: