Margaret Busby was born in Ghana and educated in the UK, becoming Britain’s youngest and first Black woman publisher when she co-founded Allison & Busby in 1967. The publishing house published many notable authors of the time, including Trinidadian historian C.L.R James, jazz writer Val Wilmer, Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah and African-Amerian writer Sam Greenlee.

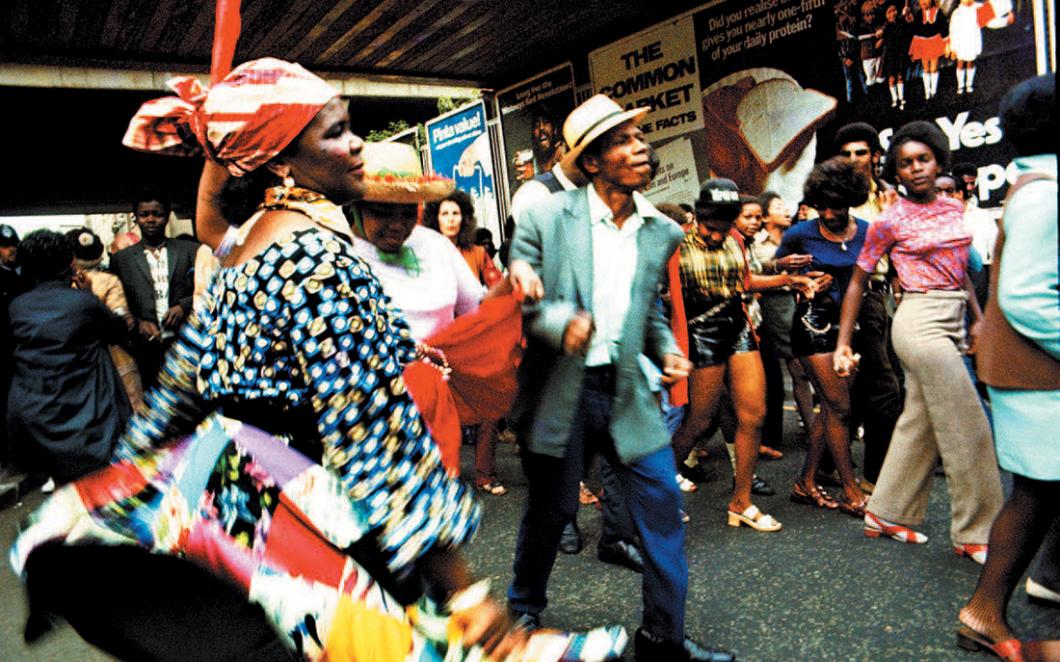

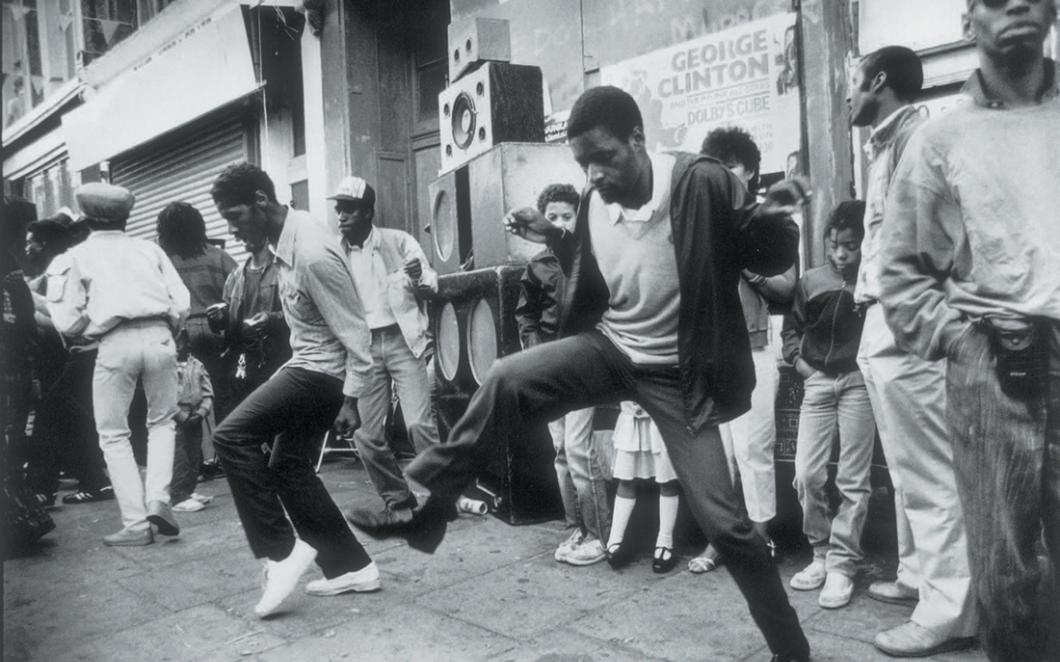

A friend of filmmaker and photographer Horace Ové - whose pioneering work forms the basis of our exhibition Get Up, Stand Up Now - here she remembers the importance of his early films and the rise of Carnival as a means of celebration and defiance for the Windrush generation.